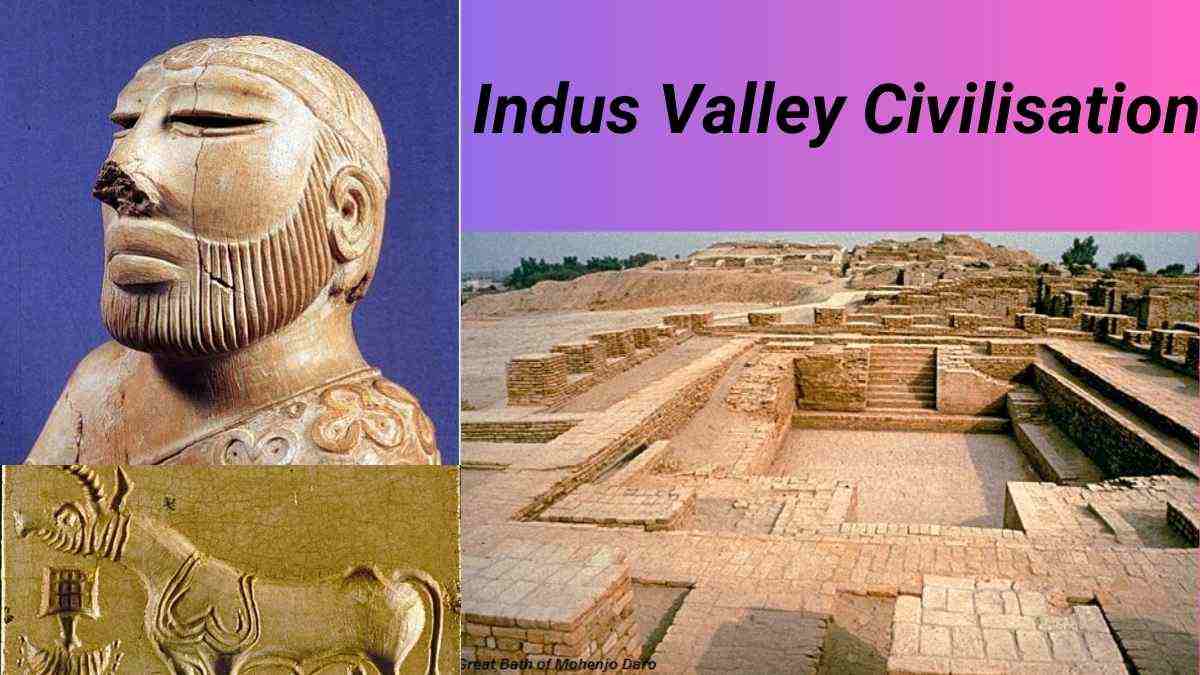

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also called the Indus Civilisation, was a significant Bronze Age civilisation that flourished in the northwestern regions of South Asia. It thrived between c. 7000 – c. 600 BCE. This civilisation was one of the three great ancient civilisations of North Africa, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and Mesopotamia. However, among the three, the Indus Valley Civilisation was the most expansive, covering vast areas of present-day Pakistan, northwestern India, and northeast Afghanistan. This article explores the major aspects of the civilization, including its urban planning, economy, trade, social hierarchy, and eventual decline.

- Observation Skill Test: If you have 50/50 Vision Find the number 3954 among 3254 in 14 Seconds?

- Optical Illusion Eye Test: If you have Hawk Eyes Find the Letter G in 16 Secs

- Optical Illusion Eye Test: Try to find the Odd Parrot in this Image

- Optical Illusion Brain Test: If you have Sharp Eyes Find the number 308 in 20 Secs

- Optical Illusion Brain Challenge: If you have Hawk Eyes Find the Number 955 among 935 in 15 Secs

Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) is also referred to as:

You are watching: Indus Valley Civilisation: Discovery, Timeline, Key Sites & Reasons of Decline

- Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation – Named after the Sarasvati River is now identified as Ghaggar in Punjab and as Chakra in the Balochistan region, which is mentioned in ancient Vedic texts and is believed to have flowed alongside the Indus River.

- Harappan Civilization – Named after Harappa, the first excavated city from this civilization in modern times.

Also Read| List of the Mauryan Empire Kings: A Brief Overview of Their Administrative Roles & Victory

Discovery of Indus Valley Civilisation

Source: harappa

Sir Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893), the first Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), conducted early excavations at Harappa in 1853, 1856, and 1872–73. His work produced the first site plan and identified key areas still referenced today. Cunningham documented Harappa’s vast ruins, including its mounds, structures, and artifacts, notably a unicorn seal with unknown inscriptions. However, his primary interest in Buddhist remains prevented him from recognising the site’s true antiquity. Later, Sir John Marshall’s excavations confirmed Harappa as part of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Cunningham’s findings are crucial for early Indian archaeology.

Source: harappa

His work is detailed in books like “The Bhilsa Topes” (1854) and “The Ancient Geography of India” (1871), where he mapped historical sites. His excavation reports in “Archaeological Survey of India Reports” (1862–1884) remain fundamental references. Despite missing Harappa’s full significance, Cunningham laid the groundwork for future archaeological explorations in India.

Later in 1920, Daya Ram Sahni started excavation at Harappa in the Montgomery district of West Punjab, and in 1921, R.D. Banerjee at Mohenjodaro in the Larkana district of Sindh. They found evidence of advanced civilisation in the region. Further, large-scale excavations were carried out under Marshall in 1931 and later in 1940 and 1946 by Vats and Wheeler. As the Indus Valley Civilisation was part of the Chalcolithic age, i.e., copper, it reflects that the Harappans were not aware of iron.

Also Read| Gupta Empire: History, Governance, Economy & Decline: All You Need to Know

Major Developments in Harappan Archaeology

|

Year |

Developments |

|

1875 |

Alexander Cunningham documented the discovery of a Harappan seal. |

|

1921 |

Daya Ram Sahni initiated excavations at Harappa, marking the first systematic dig of the site. Excavations also commenced at Mohenjodaro. |

|

1925 |

R.E.M. Wheeler conducted excavations at Harappa, contributing significantly to the understanding of its urban planning. |

|

1946 |

S.R. Rao led excavation efforts at Lothal, uncovering its dockyard and trade links. |

|

1955 |

B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar carried out excavations at Kalibangan, revealing early agricultural practices and fire altars. |

|

1960 |

M.R. Mughal undertook extensive explorations in Bahawalpur, Pakistan, identifying numerous Harappan settlements. |

|

1974 |

A team of German and Italian archaeologists conducted surface surveys at Mohenjodaro, gathering new insights into its urban structure. |

|

1980 |

An American archaeological team commenced excavations at Harappa, focusing on settlement patterns and trade networks. |

|

1986 |

R.S. Bisht initiated excavations at Dholavira, unearthing its unique water management system and large-scale urban infrastructure. |

Chronology of Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) had social hierarchies, writing, planned cities, and trade which is classified into Pre, Early, Mature, and Late Harappan phases

|

Period |

Characteristics |

Key Sites |

|

Pre-Harappan (7000-3500 BCE) |

– Nomadic people beginning to lead a settled agricultural life – Early farming and animal domestication. – Small settlements with basic trade networks. |

Mehrgarh, Rehman Dheri, Balochistan |

|

Early Harappan (3500-2600 BCE) |

– Expansion of settlements in hills and plains. – Use of copper, wheel, and plough. – Large number of villages, early trade networks. |

Kot Diji, Amri, Dholavira, Kalibangan |

|

Mature Harappan (2600-1900 BCE) |

– Development of large cities with uniform bricks, weights, seals, and pottery. – Planned townships, drainage systems, and long-distance trade. – Peak urbanisation with large centres. |

Harappa, Mohenjodaro, Lothal, Rakhigarhi |

|

Late Harappan (1900 BCE onwards) |

– Decline of urban centers, abandonment of cities. – Writing disappeared, inter-regional trade declined. – Continuation of some crafts and pottery traditions. |

Manda, Sanghol, Alamgirpur, Daulatpur |

Geographical Extent

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) predates the Chalcolithic cultures and is significantly more advanced. It emerged in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. The Sindh region played a crucial role as the central zone of the pre-Harappan culture. During its mature phase, the civilisation expanded further into Sindh and Punjab, primarily along the Indus Valley, before spreading southwards and eastwards. The civilisation covered an estimated 1,299,000 square kilometres, forming a triangular area. To date, nearly 1,500 sites have been identified across the subcontinent.

The term Indus Valley Civilisation was coined by Sir John Marshall, who was the first archaeologist to describe this ancient culture.

Major Sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation

Harappa (Punjab, Pakistan)

Source: harappa

- Discovered in 1921 on the banks of the Ravi River by Daya Ram Sahni.

- The first excavated site led to the initial naming of the civilisation as Harappan Culture.

- Charles Masson (1826) and Alexander Cunningham (1853, 1873) were early observers.

- Key findings:

- Six granaries are located outside the citadel.

- Barracks or rows of single-roomed quarters beneath the citadel walls.

- There were two separate kinds of burial practices: those found in R-37-type cemeteries and those in H-type cemeteries.

- Artifacts include a lingam and yoni symbol, a seal depicting a virgin goddess, a bronze mirror, and a red sandstone torso of a dancing female.

- The oldest Harappan site in India is believed to be Bhirrana (Haryana), as per the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Mohenjodaro (Sindh, Pakistan)

Source: harappa

- Discovered in 1922 by Rakhal Das Banerji on the Indus River.

- In Sindhi, “Mohenjodaro” means “Mound of the Dead”.

- Notable structures:

- Great Bath – a rectangular water tank (39 ft length, 23 ft width, 8 ft depth) with steps, changing rooms, and drainage systems.

- Great Granary – a brick structure measuring 45 metres in each direction, featuring air spaces between walls for ventilation.

- Oblong multi-pillared assembly hall and large administrative buildings.

- Artifacts:

- Pashupati seal, bronze statue of a dancing girl, steatite image of a bearded priest, Mother Goddess figurines, unicorn seals, clay dice, and a granary.

Dholavira (Kutch, Gujarat, India)

Source: gujarattravelagent

- Excavated in 1968 by Jagat Pati Joshi.

- Known for the world’s oldest signboard, the Dholavira signboard.

- Featured an advanced water conservation system with dams, reservoirs, and rainwater harvesting structures.

- The site received recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2021.

Table of Key Harappan Sites and Findings

|

Site |

Location |

Excavated By |

Year |

Major Findings |

|

Harappa |

Punjab, Pakistan (Ravi River) |

Daya Ram Sahni |

1921 |

Granary, workmen’s quarters, terracotta figurines, pottery with Indus script, copper bullock cart, limestone weights, cemetery burials, furnace remains, superficial evidence of horse. |

|

Mohenjodaro |

Sindh, Pakistan (Indus River) |

RD Banerjee |

1925 |

Great Bath, granary, Pashupati seal, Bronze Dancing Girl, steatite statue of a bearded priest, unicorn seals, woven cloth fragment. |

|

Sultagendor |

Balochistan, Pakistan (Dasht River) |

See more : You are highly intelligent if you can find the mistake in the restaurant image in 6 seconds! Auriel Stein |

1929 |

Trade center between Harappa and Mesopotamia, flint blades, stone vessels, shell beads, arrowheads, pottery, and horse remains. |

|

Chanhudaro |

Sindh, Pakistan (Indus River) |

NG Majumdar |

1931 |

Bead-making factory, inkpot, dog’s footprint chasing a cat, cart with a seated driver; only site without fortifications. |

|

Rangpur |

Gujarat, India (Madar River) |

MS Vats, SR Rao |

1931, 1957 |

Evidence of Harappan culture, a site without a citadel. |

|

Amri |

Sindh, Pakistan (Indus River) |

NG Majumdar |

1935 |

Post-Harappan culture, rice husk, six pottery styles, evidence of antelope and rhinoceros. |

|

Kot Diji |

Sindh, Pakistan (Indus River) |

Fazal Ahmad, Ghureey |

1953-1955 |

Steatite seal, ox figurine, terracotta beads. |

|

Kalibangan |

Rajasthan, India (Ghaggar River) |

Amlanand Ghose |

1953 |

Ploughed field, fire altars, granary, wooden drainage system, camel bones, brick structures, earthquake evidence. |

|

Lothal |

Gujarat, India (Bhogva River) |

SR Rao |

1955 |

Dockyard, bead-making workshop, fire altars, ivory weight balance, terracotta horse figure, rice husk. |

|

Ropar |

Punjab, India (Sutlej River) |

YD Sharma |

1953 |

Five cultural phases, dog buried with humans, stone and mud houses. |

|

Alamgirpur |

Uttar Pradesh, India (Hindon River) |

YD Sharma |

1958 |

Pottery, copper tools, plant fossils, animal bones. |

|

Surkotada |

Gujarat, India |

JP Joshi |

1964 |

Horse bones, stone-covered beads, ornaments. |

|

Rakhigarhi |

Haryana, India (Drishadvati River) |

Surajbhan |

1969 |

Largest Harappan site, fire altars, cylindrical seals, terracotta wheels. |

|

Banawali |

Haryana, India (Fatehabad District) |

RS Bisht |

1974 |

Radial street pattern, barley grains, toy plough, beads, drainage remains. |

|

Dholavira |

Gujarat, India (Rann of Kutch) |

RS Bisht |

1990 |

Three-part city layout, giant water reservoir, unique water conservation system, Indus script signboard. |

|

Balakot |

Balochistan, Pakistan (Arabian Sea) |

George F Dales |

1973-1979 |

Early Harappan artifacts, brick structures, bead-making workshop. |

|

Desalpur (Gunthli) |

Gujarat, India (Kutch) |

SR Rao, A Ghosh |

1963 |

Brown pottery, terracotta and copper seals. |

Key Features of Harappan Cities

1. Urban Planning and Architecture

- Followed a grid pattern, with streets intersecting at right angles, forming rectangular blocks.

- Cities were divided into two sections:

- Citadel (Upper Town) – possibly for administrative and religious purposes.

- Lower Town – the residential and commercial hub.

- Buildings were constructed primarily with baked bricks; stone buildings were absent.

- No round pillars; granaries were found in southern sites like Kalibangan.

2. Advanced Drainage System

- Every house had bathrooms and courtyards with a drainage system.

- Underground drains connected all houses to the street drains.

- Brick or stone slabs covered the drains, with manholes for cleaning.

- At Banawali, remains of streets and drainage systems were found.

3. Social and Political Organisation

- A highly developed urban society consisting of priests, merchants, artisans, peasants, and labourers.

- Men wore cotton garments, occasionally wool, while women adorned necklaces and bangles.

- A vanity case from Harappa suggests women engaged in artistic expression.

- No central ruler; was likely governed by merchant classes, unlike Mesopotamian city-states.

- No evidence of a standing army.

4. Religious Practices

- Proto-Shiva (Pashupati) was an important deity, often depicted in a yogic posture.

- Fire worship was observed at Kalibangan and Lothal but not at Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

- Ritual bathing in the Great Bath of Mohenjodaro may indicate spiritual purification rites.

Burial Practices

The disposal of the dead was an essential religious activity in Harappan society. The burial orientation was usually north-south, and graves often contained ornamental items such as:

- Shell bangles

- Necklaces

- Earrings

- Copper mirrors

- Pearl shells

- Antimony sticks

- Earthen pots

Unique Burial Practices by Site

|

Site |

Burial Type |

|

Mohenjodaro |

Complete, fractional, and post-cremation burials |

|

Kalibangan |

Circular and rectangular graves, pot burials |

|

Surkotada |

See more : GT Team 2025 Players List, Price: Check Complete Gujarat Titans Squad and Overview Pair burials |

|

Lothal |

See more : GT Team 2025 Players List, Price: Check Complete Gujarat Titans Squad and Overview Pair burials |

|

Harappa |

East-West axis burials, R-37, H cemetery, coffin burial |

Economic Life

The economy of the Harappan civilisation was primarily based on irrigated agriculture, livestock rearing, diverse crafts, and active trade, both domestic and international.

Key Economic Features

- Agriculture: Main occupation, with fertile land due to river floods.

- Trade: Barter-based, with well-regulated weights, measures, and trade routes.

- Capital Cities: Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

- Port Cities: Sutkagendor, Dholavira, Lothal, and Alhadino.

Agriculture

- Seeds were sown in November, and harvesting took place in April.

- Wooden ploughs and stone sickles were commonly used.

- Irrigation Techniques:

- Gabarbands (dams) and Nalas (water storage structures) were used in Baluchistan.

- Evidence of irrigation canals at Dholavira and Shortugai.

- Major Crops Cultivated:

- Wheat, barley, peas, dates, sesamum, mustard.

- Millets: Bajra, ragi, jowar.

- Major rice husks were discovered in Lothal and Rangpur.

- Harappans were pioneers in cotton cultivation, referred to as Sindon by the Greeks.

- Absent Crops: Sugarcane was not cultivated.

Domesticated Animals

|

Animals Domesticated |

Animals Hunted |

|

Buffaloes |

Antelope |

|

Sheep |

Boar |

|

Oxen |

Deer |

|

Ass |

Gharial |

|

Goats |

Fish |

|

Pigs |

|

|

Elephants |

|

|

Dogs and cats |

|

|

Camels (found at Kalibangan) |

|

|

Horses (evidence found at Surkotada) |

Trade and Commerce

The Harappans engaged in extensive trade, both within their region and with foreign civilisations.

Features of Trade

- Based on the barter system.

- Key Trade Indicators:

- Seals, weights, uniform script.

- Granaries for storage.

- Major Trade Partners:

- Meluha (ancient Indus region) is mentioned in Sumerian texts.

- The intermediate trading stations were Dilmun (Bahrain) and Makan (Makran coast).

Imports by the Harappans

|

Material |

Source |

|

Gold |

Afghanistan, Persia, Karnataka |

|

Silver |

Afghanistan, Iran |

|

Copper |

Baluchistan, Khetri (Rajasthan) |

|

Tin |

Afghanistan, Central Asia |

|

Agates |

Western India |

|

Chalcedony |

Saurashtra |

|

Lead |

Rajasthan, South India, Afghanistan, Iran |

|

Lapis Lazuli |

Badakhshan, Kashmir |

|

Turquoise |

Central Asia, Iran |

|

Amethyst |

Maharashtra |

|

Jade |

Central Asia |

|

Carnelian |

Saurashtra |

Art and Architecture

The Harappans, though primarily utilitarian, displayed an impressive artistic sense.

Harappan Pottery

- Appearance: Bright or dark red, sturdy, and well-baked.

- Types:

- Glazed

- Polychrome

- Incised

- Perforated

- Knobbed

- The engraved script was present on pottery.

Harappan Seals

- Made from steatite (soft stone).

- Innovative cutting and polishing techniques.

- Common Motifs:

- Animals

- Unicorn (most common)

- Short inscriptions

Notable Seals

- Pashupati Seal:

- Found at Mohenjodaro.

- Depicts Proto-Shiva seated in a yogic posture.

- Surrounded by animals (elephant, tiger, rhinoceros, buffalo, deer/goats below).

- Shows religious significance.

- Bull Seal: Found at Mohenjodaro.

- Over 2000 seals were recovered from various sites.

- Indus seals were discovered in Mesopotamian cities like Ur, Kis, Susa, and Logas.

Technology and Tools

The Harappans used a variety of tools and devices, mainly made from copper, bronze, and stone.

Common Tools

|

Material |

Tools Used |

|

Copper/Bronze |

Axes, chisels, knives, spearheads, arrowheads |

|

Stone |

Hooks for fishing, daggers, knives |

|

Factory Sites |

Sukkur in Sindh |

Jewellery and Beads

- Harappans adorned themselves with beads made from agate, turquoise, carnelian, and steatite.

- Jewellery Findings:

- Workshop evidence at Chanhudaro.

- Gold and silver beads were found.

- Barrel-shaped beads with trefoil patterns.

- Mohenjodaro’s hoard included gold fillets and silver dishes.

Script and Language

- Discovered in 1853.

- Undeciphered pictographic script.

- Approx. 250-400 pictographs.

- Writing Style: Boustrophedon (right-left in the first line, left-right in the second line).

- A signboard with 10 pictographs was found at Dholavira.

Terracotta Figurines

- Fire-baked clay is used for creating toys and worship objects.

- Animal figurines: Monkeys, dogs, sheep, cattle, bulls (humped and humpless).

- Human figurines: Male and female.

- Boat models: Found at Mohenjodaro and Lothal.

What caused the Indus Valley Civilisation to decline?

Several theories have been proposed to explain the downfall of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Some of the most significant include:

1. Environmental Changes

|

Factor |

Details |

|

River Drying Up |

The Ghaggar-Hakra River, identified with the Sarasvati River mentioned in the Vedic texts, is believed to have dried up around 1900 BCE, leading to water scarcity and mass migration. |

|

Flooding |

Evidence of significant silting at sites like Mohenjo-daro suggests that major floods could have devastated settlements, causing displacement of the population. |

2. Decline in Trade

- The Late Harappan period coincided with the Middle Bronze Age in Mesopotamia (2119–1700 BCE).

- The Sumerians, the main trading partners of the Indus Valley Civilization, were engaged in conflicts such as expelling the Gutians and facing conquest by Hammurabi (1792–1750 BCE).

- In Egypt, instability during the Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 BCE) led to economic disruptions, weakening trade links with the Indus Valley.

3. The Aryan Invasion Theory

One of the most debated theories regarding the fall of the Indus Valley Civilisation is the Aryan Invasion Theory.

Origins of the Aryan Invasion Theory

- Western scholars in the 18th and 19th centuries interpreted Vedic texts, leading to the idea that India was invaded by a superior “Aryan” race.

- Sir William Jones (1746–1794 CE) proposed that Sanskrit and European languages shared a common linguistic source, later termed Proto-Indo-European.

- Scholars speculated that a light-skinned race from Europe migrated southward, influencing Indian culture.

Influence of Racialist Views

- Joseph Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882 CE), a French writer, promoted the idea of “Aryan superiority” in his work An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1855 CE).

- His ideas influenced figures like Richard Wagner and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, eventually impacting Nazi ideology.

- Max Müller (1823–1900 CE), a German philologist, clarified that “Aryan” referred to linguistic groups, not race. However, his views were misinterpreted to support racial theories.

Excavations & Validation of the Theory

- Sir Mortimer Wheeler, a British archaeologist, excavated Indus sites in the 1940s and suggested that the “Aryan invasion” could have caused the downfall of the civilization.

- His interpretation of skeletal remains at Mohenjo-daro supported the claim of a violent conquest.

- However, later studies debunked these claims, as no evidence of large-scale warfare was found.

Modern Perspectives: Was It an Invasion or Migration?

Recent archaeological findings reject the Aryan Invasion Theory in favour of the Aryan Migration Theory:

|

Aspect |

Aryan Invasion Theory |

Aryan Migration Theory |

|

Nature of Arrival |

Violent conquest |

Peaceful migration and assimilation |

|

Impact on IVC |

Destruction of cities |

Gradual cultural integration |

|

Evidence |

No confirmed proof of war |

Linguistic and genetic traces of Indo-Iranian influences |

Key Evidence Against the Aryan Invasion Theory

- George F. Dales (1960s CE) examined Wheeler’s findings and found no evidence of war or violent deaths.

- Skeletal remains did not show signs of battle wounds.

- No large-scale military structures or weapons indicating an invasion were found at Harappan sites.

- Genetic studies suggest gradual Indo-Aryan migration rather than an armed conquest.

Conclusion

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) was an extraordinary Bronze Age society that excelled in urban planning, trade, and technological advancements. Its extensive geographical spread and well-organised cities like Harappa, Mohenjodaro, and Dholavira highlight its significance. Despite its decline, the IVC left a lasting imprint on South Asian culture and history. Its seals, drainage systems, and architectural marvels continue to fascinate scholars, offering deep insights into early human civilisation.

Source: https://dinhtienhoang.edu.vn

Category: Optical Illusion